use gh and tell me how many PRs I have authored the last 3 weeks. from these PRs how many are merged? what was the total of added and removed lines?

Your PR Statistics (Last 3 Weeks)

- Total PRs authored: 31

- Merged PRs: 27 (87% merge rate)

- Total lines added: 4,095

- Total lines removed: 2,758

- Total lines changed: 6,853

You've been quite productive! Most of your PRs from the last 3 weeks are merged, with a solid mix of refactoring and feature work.

Up until now the main way of using LLMs was through chat. Every time I wanted to do a deep dive on a technical issue I was starting a conversation through which I was getting a better understanding both on the code and the way it should be used.

I had played with the agent tab of copilot in android studio but never given it too much time. That was the reason I believed that it is not that good!

So, I decided to give it a real shot and use it foul time, on production code, in a project that is important. The goal was to write as little code as possible.

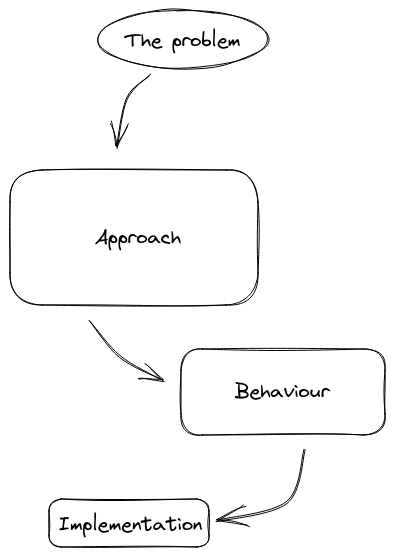

The workflow I ended up having

- Understand the task at hand and create a mental model of the solution.

- Figure out the steps I need to make in order to implement the solution. If the steps are too many I break them into groups.

- Start writing these [group of] steps in a prompt where I ask the agent to provide me a plan with the intended changes.

- Review the plan, ask the agent to make adjustments (repeat this step as many times as needed).

- Ask the agent to save the plan in a markdown file.

- Ask the agent to execute the plan.

- Review the changes.

- If something trivial needs to be changed I do it myself, if the change cascades through many files I tell the agent to do it.

- In the second case I also request an update to the plan.

- Final review, commit and push.

The prompts must not be too detailed but also not too general. For example:

Take a look at <file #1> and <file #2> and give me a plan with all needed changes in order to:

1. Start <component #1> as disabled

2. Enable it every time the user selects an address (<component #2>) or

3. Enable it every time the user is typing a new zipcode (<component #3>)

Mistakes

It goes without saying that to end up in the above workflow I did many mistakes. Here are the big ones.

Provide the outcome

At first my prompts were a simple description of the outcome I wanted. I thought it will figure things out, make the necessary connections and write exactly what we need. Nope. The agent knows what you allow it to and when it can’t find something it simply creates random solutions.

Straight to the execution

My interaction with the agent was starting by asking it to do something. No plan at all. In simple cases this might be fine but when having a change that touches many components, a simple adjustment, after the agent’s work, might end up in updating a lot of code or in more adjustments.

Getting greedy, asking too much

After making some progress and saw how effective I was I got greedy. I started asking too much from the start and ended up with massive PRs that included changes often unrelated to each other.

Tips

Always have a plan first

- For me having a plan gives me ease. I am more certain that things will be done as intended because they will be done they way I want to!

- Through the process of making the plan there will be times that you will understand better the code at hand and figure out missing cases.

- Especially for repetitive tasks the plan speeds things tremendously:

I had to migrate a few screens from one pattern to another. I did the first migration using the agent (through a plan etc) and when finished I asked it to change the plan in such a way that will accept “parameters”. After that I just fed the updated plan with the next screen to the agent. - It is a memory that can be fed in any agent, in a clean context window, at any time.

Use the agent to figure things out

Some times in order to build the mental model for the solution you need to understand the code better. Use the agent to do that. See how it articulates things and then ask it to save its findings in a file. That file can be part of the plan:

see how component A works by reading file <name>

Always review the code

Perhaps the most important tip of all. Don’t add code to the project that you don’t know what it does. Always review what the agent did. Make sure that it follows the project’s conventions and standards. The fact that it was written by an agent does not mean that it is not your code. You are responsible for it. It is your solution, you just used a different medium to implement it.

Explore more, it is fast now

The benefit of having a tool that implements your thoughts way faster than you is that you can explore multiple solutions! Use git to make different branches/checkpoints and try every approach you thought of.

Keep things small

You can use an agent to implement an entire task but if you break it and do groups of changes then your reviews will be easier and quicker which means that your understanding of the changes will be better.

Bonus

I keep a repo with the Gilded Rose kata. Every now and then I create a new branch and practice on the kata.

This time the practice required to use only an agent. You can see the branch here and the prompts I used here (i asked the agent to save them to a file).